Georgette (1876/11/31)

Calgardup Bay

Georgette was built as a collier by McKellar, McMillan & Co. at Dumbarton in October 1872. When originally launched the steamer had the official number 68004. It was clinker built and had one deck, four bulkheads and a round stern. The vessel, which was cemented, was rigged as a 2-masted topsail schooner with a capacity of 460 deadweight tons. It had a raised quarterdeck 19.2 m long and a forecastle 6.9 m long. Smith Bros & Co., Glasgow, built the 2-cylinder compound engine, which gave 24 HP per cylinder.

Thomas Connor of Fremantle bought the single screw steamer in the UK for £14 000, the vessel arriving in Fremantle in September 1873. The newspaper reported that it was to be ‘re-christened the Western Australia’ (Inquirer, 30 July 1873: 2d), but this obviously did not occur. The following month it grounded on Murray Reef, springing some of the plates, and was in imminent danger of sinking as it steamed to Careening Bay for repairs. After these repairs a regular contract mail service was established between Champion Bay and Albany, calling in at intermediate ports. This contract was operative until it expired in September 1876. During this period the Georgette also made some voyages to Adelaide where the vessel was overhauled, especially after being stranded on the reef in October 1873. On 29 November 1876 Connor mortgaged the Georgette to John McCleery, merchant of Fremantle, for £2?000.

On 24 November at Bunbury the Georgette took on a cargo of 145 loads of jarrah valued at £870. Some large pieces were 30 cm square and over 9 m long, and during the loading one of these pieces fell into the hold. The steamer sailed that night for Fremantle where further cargo consisting of 25 bales of leather, two casks of whale oil and 260 hides was loaded. The total value of all the cargo was £1 257.10s. The Georgette departed Fremantle on 29 November for Adelaide via Bunbury, Busselton and Albany. On board were 50 passengers, two for Bunbury and 48 for Adelaide. The stops at Bunbury and Busselton were of short duration, and it left the latter port during the afternoon of Thursday 30 November.

THE LOSS

About midnight on 30 November the Georgette developed a leak. None of the pumps on board, including the steam pump, worked, and the water rose so that at 4.00 a.m. on Friday 1 December Captain Godfrey had the crew and some of the passengers bail with buckets. The vessel was steered towards the coast, but at 6.00 a.m. the rising waters put the fires out and the steamer lost all power, so the sails were set and the vessel headed for the shore, still some kilometres away. A letter from James and William Dempster to their parents described some of what took place:

You will be glad to know that my brother William and I got off in the rush for life that took place at the wreck of the Georgette. After leaving Fremantle we got on all right to here (Vass), where we arrived on Thursday about eight o’clock, and started on again about 10 a.m. I noticed some of the crew pouring water into the pump of the engine before the ship started, which shows that it must have been out of order. After rounding Cape Naturaliste the sea was rather rough and so continued all night, but nothing to hurt a ship that was in the least bit seaworthy. I was on deck about 2 am, when all seemed right. I turned in again, but was awakened about half-past five by the men being sent down the lazarette to bail out the water. I think there was more noise than water at that time, as the men did not seem to have their buckets more than half full, the water at that time being not much over the ballast. We went on deck again about 6 a.m. and found that there was no less than eight feet of water in the engine room, which showed that the leak was in that compartment, no water being reported in the fore hold. The crew were bailing out with buckets, but it was gaining fast on them. The ship’s head was turned for shore and she appeared water-logged. The engine fires were extinguished by the water directly after the ship’s head was turned for land. This must have occurred between 4 and 5 am, our position being about 30 miles S.W. from Cape Hamelin. [See note at end of this section—author]

Between 7 and 8 a.m. the lifeboat was lowered, but being very leaky it was soon half full of water. The water was got under a little by bailing with a bucket, and three men and about fourteen women and children were put into it, when she was passed astern for more bailing, as she was full of water quite up to the thwarts, women and all bailing for dear life. Meanwhile my brother William saw that the smallest boat had broken away a ring bolt and was getting stove in against the steamer’s side. He slid down the other fall and called out to the crew to lower away, which was done. They threw him a bucket and passed him aft, as the boat was up to the thwarts, but before he had her free the lifeboat was again hauled alongside and some more women and children put into her. She then got under the ship’s counter and immediately filled with water. Five of the occupants made a spring for the ship’s deck, some made a rush for the side next the ship, and the boat capsized on a lot of the poor women and helpless little children.

My brother seeing the inevitable consequences of the calamity, pushed his boat up as close as he could and helped those in the water onto the boat, but he had not strength to get them in, as there were so many all on one side and the boat was very full of water. I saw him try his utmost, but the boat’s gunwale went clean underwater. The cabin boy jumped overboard but missed the boat; he then managed to get on the bottom of the lifeboat. I caught hold of an oar, pulled off my coat, and quickly jumped over the stern to go to my brother’s assistance. I was lucky enough to come up close to the boat, but on the opposite side to where the women and children were clinging to it. My brother caught hold of my hands and helped me in, and we then got the young children on board. I went aft and passed the first woman I could get hold of round the stern on to the other side, and held her there until my brother helped me get her and the others into the boat. They on board the ship pulled our boat under the steamer’s stern and the first mate got in. They then cast us off from the ship to pick up the second mate, who jumped overboard after I had got into the boat but had missed her, and was sitting on the bottom of the lifeboat with the cabin-boy.

Our first effort was to get our boat bailed out, and we had to make throwel [sic] pins before we could do anything. We then went in search of the other boat, which we soon found and pulled up close to, when those on her bottom jumped off and we soon had them on board. They were of course delighted to see us, as they were beginning to despair. By this time the Georgette was over a mile from us, heading for shore, with a freshening breeze. We had no chance of overtaking her, so we shaped our own course for shore. The sea was too high to head directly for shore, so we edged in as much as possible; James being kept constantly bailing. It was at this time that we were exposed to great danger, for the wind continuing to rise the sea had got up to a great pitch, and the difficulty of keeping the boat free increased instantly.

We were still in no enviable condition—twenty miles off the Leeuwin, in a small and very leaky boat, without sails or rudder, and only three oars, with a crew of ten adults and ten children, all wet through and miserable. I wanted to rig a blanket we had, but the others thought the sea too rough, and preferred pulling, but it was slow work with only two oars and a very heavy sea, the wind being right on our beam and freshening fast. We kept on this way until about 4 p.m., when we rigged a towel forward, which made a great alteration in our speed and kept the boat freer of water. We then got our blanket rigged, using one of the oars for a mast and a bit of batten from the boat’s bottom for a yard, and got along well until 10 p.m., when we got close in shore and were fortunate enough to find a place to land without much danger, about 15 miles south of Cape Naturaliste, the surf not running very high. We all got ashore in safety, but were all thoroughly drenched. Willie, the chief officer and two of the sailors started off shortly afterwards and obtained food and help from a neighboring [sic] homestead—Mr. Harwood’s, in reaching which Willie and the chief officer were occupied the whole night, being greatly baffled by timber tracks running in all directions (quoted in Inquirer, 10 January 1877: 3c).

Author’s note: This should read ‘Cape Naturaliste’, and was either written in error by the Dempsters or misquoted by the newspaper.

A bullock team took these particular survivors from their landing place near the Quininup Brook to Yelverton’s sawmill at Quindalup on the Saturday night. The group consisted of William Dundee (1st mate), John Dwyer (2nd mate), A. McLeod (seaman), James Noonan (cabin boy), James Dempster, William Dempster, Miss Walsh, Mrs Herbert Dixon and child, Mrs Simpson and child and Mrs Stammers and two children.

Shortly after sunrise on the Saturday 2 December the Georgette had blown onto a sandbank ‘two ship’s lengths from shore’ (Inquirer, 6 December 1876: 3a) near the mouth of Calgardup Brook where the third lifeboat was used to attempt to take a line ashore. During this attempt the boat was capsized and swamped by 2-m high waves, but recovered and returned to the steamer where some of the passengers were transferred to it, and it again headed for the shore. Once again the boat was capsized, and two local residents, Yebble @ Samuel Isaacs and Grace Bussell, rode horses into the surf to assist in the rescue of these survivors.

The schooner Ione left the Vasse at 7.00 a.m. Sunday morning to go to the scene of the disaster but was unable to reach the Georgette. It did, however, pick up some of the crew and passengers who had come ashore at Calgardup and took them to Busselton.

INQUIRY

The nautical surveyors, Messrs Storey and Owston, travelled from Fremantle aboard the steamer Start, collecting Captain Harris of the Charlotte Padbury at Bunbury en route. The three disembarked at Busselton and travelled overland to the wreck site of the Georgette.

A Court of Inquiry into the loss of the Georgette, commenced at Busselton on 21 December 1876, was made up of five members; the subcollector of Customs, William Pearce Clifton, John Brockman, J.P., George Forsyth, harbour master, William Eldridge, engineer and Navigating Lieutenant William Tooker, RN. They heard five charges brought against Captain John Godfrey, together with other charges against a further three members of the crew:

1. That without due regard for the safety of the ship he took in a large quantity of jarrah timber hastily, violently and incautiously, thereby injuring the vessel and causing her to leak, resulting in the loss of the vessel and lives of passengers

.2. That he proceeded to sea with an insufficient number of boats, these not being seaworthy.

3. That he placed passengers in a leaky boat, the upsetting of which caused the loss of several lives.

4. That his Chief Officer did not have a certificate of competency or service.

5. That the ship’s pumps were damaged and not in good working order (Henderson, 1988: 211).

The hearing concluded on 26 December, and Captain Godfrey was acquitted of all five charges, but the court found that he was guilty of a grave error of judgement in not taking further steps to ascertain the condition of the ship at 8.00 p.m. on 30 November, when the engineer reported the unsatisfactory working of the bilge pump. The first engineer was acquitted of the charge of neglect of duty in not having reported directly to the captain the unusual quantity of water in the ship. The second engineer was found guilty of neglect of duty in not having taken steps to ascertain the cause of the leak, which he had noted when he first came on watch on the evening of 30 November. The mate was found guilty of disobedience of orders in not veering the lifeboat astern, when directed to do so by the captain—loss of life resulting from such disobedience (Inquirer, Supplement, 24 January 1877: 1d).

The nautical assessors, Tooker, Forsyth and Eldridge, while concurring with the findings also considered that the captain was guilty of grave misconduct in regard to charge number three, that is, in placing passengers aboard the leaking lifeboat considering the state of the wind and sea at that time.

An assertion had been made prior to the inquiry by some unnamed passengers to the sub-inspector of police at Bunbury. They believed the ship had been deliberately scuttled. This assertion must have been investigated but dismissed at a fairly early stage in proceedings, as it was not a charge brought against the captain or crew.

The certificate of the master, John Godfrey, was suspended for eighteen months. The mate, William Dundee, had his certificate of competency cancelled. The first engineer was acquitted of the charge, but the second engineer, Joseph Hourigan, had his certificate suspended for 12 months. A newspaper later reported that these suspensions were deferred ‘pending the decision of the government as to the necessity or otherwise of further proceedings’ (Inquirer, Supplement, 24 January 1877: 1e).

The Court of Inquiry suggested that a charge of manslaughter be brought against both the master and the first mate. The mate was arrested on 27 December, brought before a court where the hearing was remanded for eight days. The captain was also charged, but ‘the warrant is stayed until further instructions is received from headquarters’ (Sub-inspector of Police, Bunbury, SRO 129, File 24/31). The outcomes of these two charges are not known.

With regard to the first charge, in his reminiscences, Happenings through the years, Edward Henry Withers wrote that he had helped to load the timber into the Georgette prior to its sailing on 30 November 1876. He claimed that the falling timber would not have damaged the hull of the steamer, as there were already three or four pieces of timber of the same size in the hold, and these would have absorbed and spread the shock. He stated that this had happened on previous occasions without causing any problem. No action was taken by the court on the first charge as it could find no evidence of ‘hasty, violent or incautious loading at Bunbury, or that any injury to the ship was caused thereby’ (Inquirer, 24 January 1877: 1d). In the opinion of Withers the Georgette had struck something after leaving Busselton, thereby damaging the hull. He was the last worker to leave the vessel at Busselton, and claimed that at that time the steamer had been very low in the water.

INITIAL SALVAGE

Sergeant Back of the Busselton Police Station reported on 2 December:

A report was received by the police from John Brockman Esqr. J.P. who lives near the wreck to the effect that the passengers & crew of the wreck Georgette was plundering the Ships Stores & passengers Luggage. I then sent a constable with chains & Handcuffs out at once with instructions to the police to render every assistance in their power and to detect plundering of property (SRO 129, File 24/31).

In January 1877 the Inquirer advertised the auction of the Georgette:

This day: Sale of the Wreck of the S.S. Georgette and her cargo of timber—Messrs. Lionel Samson & Son (Government Auctioneers).

The Wreck of the Georgette with her machinery, engines, spares, and etc., as she now lies off Calgardup Gully, near the Margaret River, about 34 miles south of Cape Naturaliste.

Also the whole of her cargo of timber consisting of 546 pcs Sawn Jarrah (about 140 loads) in sizes of 5x5 to 12x12 in lengths from 14ft to 40ft, 10 pcs hewn timber.

And LASTLY—the unsaved portion of the remainder of her cargo consisting of Whale Oil, Leather, Hides, etc.

The Whole Without Reserve Sale at noon sharp (Inquirer, 10 January 1877).

The ship’s bell from the Georgette was retrieved by two sons of Henry Yelverton, and was given to one of Yelverton’s daughters when she married the postmaster at Jarrahdale. The couple gave the bell to St Paul’s Anglican Church at Jarrahdale, but the church officials on finding that it was cracked purchased a new bell. The bell from the Georgette was then taken home by a local farmer and is now on loan to the Augusta Museum, which also holds a number of small items such as portholes and a steam pipe from the wreck. A small cabinet from the captain’s cabin is held in the Busselton Museum.

SITE LOCATION

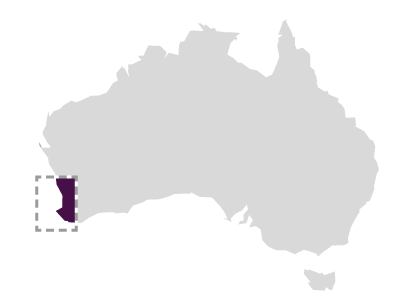

The wreck of the Georgette lies just offshore of the mouth of Calgardup Brook, south of Redgate and is marked by a cairn and plaque on the shore.

SITE DESCRIPTION

A wreck inspection on 8 February 1980 by Michael McCarthy of the Western Australian Museum reported that the wreck of the Georgette lay about 100 m from shore in 5 m of water on an axis of 100°, with the bows pointing towards the shore. During the inspection the outline of the hull was barely visible as it was heavily corroded above the sand line. The engine (with piston block torn off), propeller shaft, sternpost and the lower part of the hull were visible, together with part of the bow and an anchor winch. Part of the wood ceiling was visible just forward of amidships on the starboard side, and copper pipes and other fittings lay among the wreckage. A hand winch was seen about 5 m from the bow. Evidence of scouring results in different sections of the wreck being visible at different times.

EXCAVATION AND ARTEFACTS

In March 1964 the 4-bladed iron propeller (almost 3 m in diameter) from the Georgette was salvaged by divers, but was later lost when heavy seas buried it under sand on the beach. The bell from the Georgette is on display at the Augusta Historical Museum.

Located by members of the UEC, its engine was dismantled for the brass fittings and in March 1964 a propellor removed and dragged ashore, only to be lost. Despite a magnetomer search led by J. Green it has not been found. The bell is in the Augusta Museum.

Ship Built

Owner T. Connor

Master Captain John Godfrey

Builder McKellar and McMillan

Country Built Scotland

Port Built Dumbarton

Port Registered Fremantle

When Built 1872

Ship Lost

Grouped Region South-West-Coast

Sinking Leak developed

Deaths 12

When Lost 1876/11/31

Where Lost Calgardup Bay

Latitude -34.042317

Longitude 114.999515

Position Information Aerial GIS

Port From Fremantle

Port To Adelaide

Cargo Passengers, Jarrah, sundries

Ship Details

Engine 2-cylinder compound vertical, double-acting 48 HP

Length 46.20

Beam 6.90

TONA 211.64

Draft 3.50

Museum Reference

Official Number 10755 (I.J. Field: 68004)

Unique Number 1160

Sunk Code Wrecked and sunk

File Number 2009/0123/SG _MA-428/71

Chart Number BA 413

Protected Protected Federal

Found Y

Inspected Y

Date Inspected 1990/12

Confidential NO