Emma (1867/03)

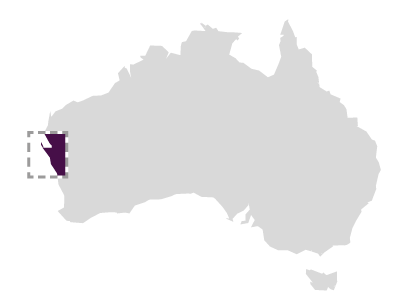

Coral Bay

The 116-ton two-masted wooden-hulled schooner Emma was built at Lowestoft in Suffolk England in 1859. It was 26.1m long by 6.2m broad, drawing 3.4 m and had one deck, a round stern and a ‘shield’ head. It’s registry was transferred to unknown owners at Fremantle in September 1865 and it was purchased by local shipowner and entrepreneur Walter Padbury in the following year. In its subsequent short career on the Western Australian coast Emma was involved in many incidents under its first two Captains; losing a man overboard on its first voyage; an anchor off the DeGrey River; colliding with a jetty at Champion Bay (Geraldton) and going aground at the Abrolhos and also at Butcher Inlet (Cossack). One of these incidents was blamed by one experienced traveller on its being fitted with compass taken from the ship Calliance which was wrecked at Camden Harbour a year or so before. It was three times the schooner’s size and to some the compass would have proved completely unsuitable. Emma was also dismasted near the South Jetty in Fremantle after striking a sand bar. After being refloated she was driven back onshore and Figure 1 is possibly a depiction of Emma or of a very similar vessel ashore at this time. After being refloated Emma underwent a refit and had new rigging before returning back to the north (Halls, 1984; Henderson, 1988, 67-71).

Early link to the north west

In 1865, soon after the first of the European settlers landed in the north District of Western Australia, the West Australian merchant and pastoralist Walter Padbury purchased Emma to service his business interests and as a transport to his new pastoral lease in the north west. He was an influential shipowner and had been one of the main agitators for settlement of the ‘North District’—the name given to all the lands north of the Murchison River. The subject of a very positive report by F.T. Gregory in 1861, it contained not one known European inhabitant at the time. In the following year Padbury landed at Butchers Inlet in Nickol Bay and then sent a party under his manager and brother-in-law Charles Nairn overland to establish a pastoral ‘run’ on the De Grey River. He then returned to Fremantle and was greeted with great enthusiasm and accolades as the pioneer of what was seen as a land of great promise.

Padbury had been quickly followed into the region by many other hopefuls, including John and Emma Withnell, who established the aptly-named Mount Welcome station, and as two examples pertinent to the Emma story John Wellard’s party chose a block later called Pyramid Station some 25 miles from Withnell’s and a group from Portland Victoria established ‘Indernoona’ station further inland. Other than these small private concerns three ‘large’ companies in the North District also formed to take advantage of the very generous land regulations designed to foster European settlement. These were the Western Australian-based Roebuck Bay Pastoral and Agricultural Association, and two Melbourne-based groups the Camden Harbour Pastoral Association and the Denison Plains Pastoral Company. They intended to settle in the Kimberley region further north but were beset with so many difficulties that soon after landing, many of their settlers and staff left and landed at Nickol Bay where they joined those already in residence there. Then government in the form of the newly appointed Resident Magistrate, R.J. Sholl, also transferred south arriving from the failed Camden Harbour settlement in the barque Tien Tsin with his son and secretary Trevarton, in February 1865. In May he was followed into Nickol Bay by C.E. Broadhurst and his family with what were be the advance guard of the Denison Plains Pastoral Company, many with family and some with very young children. They then settled in the region only to find it slowly sink into the depths of a severe and prolonged drought causing great personal suffering to all in the district. The desperate circumstances were only partly eased by the gradual development of a de facto township at the cluster of huts surrounding Withnell’s homestead. In August 1866 this became the township of Roebourne. Also relieving the shortages and some of the suffering were the arrivals of Padbury’s cutter Mystery under Peter Hedland and his schooner Emma with stores and news from the south.

In preparation for its March 1867 voyage down to Fremantle under Captain Badcock, wool from the defunct Roebuck Bay Pastoral Association was loaded together with eight tons of pearl shell belonging to a former Denison Plains Company man W.F. Tays. It was to be amongst the first shipments of wool and certainly the first large shipment of shell from the region, heralding a new era in the north and rendering Padbury’s Emma doubly important in the history of the north-west.

Emma and the pearling industry

Initially ‘dry’ pearling (or harvesting by beach-combing or wading in the shallows) was the fashion at Nickol Bay. By this means, the shallow beds adjacent to the shore were exploited at low tide. Apparently having prior knowledge of methods used elsewhere e.g. at Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Tays and his partner Augustus Seubert, obtained a boat by entering a partnership with a pastoralist who had obtained the boat in exchange for fresh meat from an American whaleship. Tays and Seubert had also located productive beds in shallow water close to shore, apparently with the aid of local Aborigines. These two factors were keys to success in this phase of the industry. Many followed their example and in November 1866 Padbury sent a large boat up in the Emma, for use in the pearl fishery. He too proved successful. The record is very incomplete and a great deal of the activity at Nickol Bay at this time, would not have been recorded. All the officials, diarists and commentators, such as the Robert and Trevarton Sholl were stationed some kilometres inland. It also needs to be noted that many pearlers would have been secretive, desirous of anonymity or keen to establish a commercial advantage at this time.

With 12 tons of shell hidden on the coast, worth around £100 per ton landed in London (then the equivalent of a mid-level government servant’s annual wage), Tays informed Trevarton Sholl and apparently Charles Broadhurst, then the acting Resident Magistrate, that he had thoughts of going to Victoria to purchase a small craft and form a pearl fishing company. He then took passage on board the Emma with much of that cache.

The loss of the Emma

The schooner left Mystery Landing in Butcher’s inlet (later renamed Cossack) and cleared Tien Tsin Harbour (Port Walcott) with its cargo and with 42 souls on board including seven crew. On board were Tays; seven military pensioners from the Roebuck Bay Pastoral and Agricultural Association; Padbury’s brother-in-law Charles Nairn; and the Resident Magistrate’s son T. C. Sholl. According to Chris Halls (1984), there were also ‘four policemen in charge of two or three Aboriginal prisoners and three free natives’. Also on board were the master and one of the crew of the New Perseverance a 105 ton schooner that had run aground the shores of Butcher’s Inlet while carrying stock and dismantled buildings from the Roebuck Bay Company (Perth Gazette, 12/7/1867). Being lightly loaded for its tonnage with only the shell, lugage and the wool in its holds, Emma also took on board an estimated 25 tons of iron ballast ( R. J. Sholl diaries and Occurrence Books, 16/8/1867, CSR 603/ 92;108).

Given that a sailing voyage down to Fremantle took an average of 50 days and that the return trip back north around 30, Badcock had expected to be back at Tien Tsin at the very latest after two months with the much-needed supplies for the struggling settlers. After leaving Cossack on 3 March 1867 Emma disappeared with all hands, however, leaving the struggling settlement at Nickol Bay despondent at the loss of over a quarter of their number, near to starvation and without communications.

With the drought deepening and famine setting in, Sholl sent a party overland to Champion Bay for a relief ship. In his private diaries and in his official despatches from this time Sholl records both his grief at the loss of his son and also some of the speculation surrounding the disappearance of the Emma and that of the Cutter Brothers which was also missing at the time (Green, this volume). Sholl noted in his reports that Emma had a ‘defective mainmast’ and that Badcock had planned to sail around Ritchie’s Reef (the Trial Rocks off the Montebello Islands) before heading in to travel closer to shore. He believed that Emma may have been dismasted in strong winds to then float helplessly at the mercy of the wind and seas. In effect the ship, if it had not foundered at sea, could have fetched up on any part of the mainland, or on outlying reefs between Cossack and Fremantle.

The schooner Flying Foam was subsequently despatched and two days after its departure the 12 July edition of the Perth Gazette graphically illustrated the prevailing thoughts.

If she was wrecked on one of the island lying off the coast. some of the people would have probably have safely gained the shore, but were that the case we shudder at the thought of the miserable lingering torture they must have gone through; allowing that all the stores of the vessel were saved, four months must have brough starvation, and perhaps perishing from want of water; death from immediate drowning on being wrecked is the more preferable death we could wish them

The schooner Heather Bell which arrived with a cargo of guano at Sydney in August reported seeing wreckage on Bedout Island north west of the DeGrey, sparking a search. Nothing was found. Though all hope of there being survivors faded with the passing of time, speculation about the fate of Emma and its contingent continued for well over a century. It appears that parts of the wreck may actually have been sighted, however, for nearly a decade after the disappearance Charles Tuckey followed up a report from a local Aboriginal man of three wrecks including one describing survivors from a wreck getting ashore only to be killed . The report read:

To ascertain if possible whether the wrecks really existed Mr Tuckey took his vessel inshore as close as he considered prudent after rounding the Cape and by the aid of a telescope made out distinctly the ribs of a vessel lying on the beach. The place is situated about 100 miles to the south of the Cape, between Point Cloates and Cape Cuvier, where a reef of fifteen to twenty miles in length and generally undefined on the charts, runs out to seaward.

Here the correspondent is describing the area north of Coral Bay. According to Halls, in concluding his examination of what he described as ‘one of Western Australia’s most puzzling mysteries of the sea’ . . . nothing was done nor, it seems, were any steps taken to confirm his story by an official examination of the supposed wreck site’. (1984:23). Three years later there appears to have been similar official inaction after the 5 November 1879 edition of the Inquirer newspaper carried another more gruesome report thus:

Captain of the Schooner Nautilus, Mr John Tapper, found on the beach between Shark Bay and Cossack, a portion of a vessel, evidently wrecked many years ago, the remains of which were strewn upon all parts of the shore. Close to the stern Tapper discovered no less than 5 human skeletons, but no indications of the name of the vessel or her destination’.

As a result no trace of the Emma or any clues to its fate were ever found until recent times.

A wreck believed to be the Emma is found

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Museum received three separate reports of possible wreck with off Point Maud in the vicinity of Coral Bay. These were from local diver Serge Katarski and then by Perth-based divers Jim Sellers, and Dean Whiting. All three reports were believed to refer to the same site. Attempts to join with Mr Katarski soon after hisreport was received failed when he was forced to depart for New Zealand the day before the Museum’s tream arrived. Eventually objects were brought in to the Museum for identification by Mr Sellers which led Scott Sledge, the then Inspector of Wrecks, to conclude that the report ‘suggests very strongly that the wreck is that of a lugger [referring to] ( YM [yellow metal] sheathing, tacks, small bolts . . . and part of YM hard-hat diving dress collar with the word “FRONT” stamped into it). Given this tentative and at the time quite reasonable assessment the report was not be given a high priority. As a result and given that an inspection of a such a remote site would prove a very costly exercise, it was decided that (as per standard practice) the Museum would await the gathering together of a suite of reports in the region or en route to better use the funds available.

In August 1987 an informal report was relayed to staff from a Brian Ingram of Esperance. This was of a site off False Hill and Whaleback Hill that he had been shown by a local spearfisherman. Ingram described it as being in 10-12 feet of very rough water, and seeing forks, cannons in slightly deeper water to the south, heavily encrusted timbers, ‘no coins’, anchors approximately 10-15 feet long approximately 20 feet apart, one an ‘Admiralty type with ring on end’ in an area with lots of ‘bombies’ in reef and sand areas. After being contacted with a request to file a report of finding, Mr Ingram indicated that he felt that the wreck was closer to Coral Bay than he had earlier indicated, most likely at the Katarski/Sellers/Whiting site. Nothing further transpired as a result, though later he was written to on the possibility he had seen another significant site.

In May 1988, utilising a sketch made from Mr Sellers’ description, a team lead by the author, who was then Inspector of Wrecks, located and examined a wreck now understood to be the Emma. The remains were found on a flat corraline reef north of Coral Bay at the entrance to which at mid tide is covered by c. 2-3m of water but as the tide lowers becomes completely undiveable in the current and broken waves. The site was heavily encrusted in growth and concretions and is so shallow that at low water spring tides it is expected that some of the anchors would become visible. The wreck was found to lie on a E/W axis with the position of the bow indeterminate due to the location of anchors and hawsepipes at either end. There were seven anchors visible some with stocks stowed. The subsequent inspection report reads thus:

Iron stocked anchors ranging in size from 1.2 to 1m overall. Two of these have stocks set and a further two have each lost a fluke and appera to have been cargo or ballast. A substantial chain moundand heavily concreted ballast/cargo mound appears in three distinct sections each to a height of circa 1m Brocken or distored knees are visible throughout. These are fastened with copper through bolts to timbers once around 4 inches thick. One iron knee rider 3” by 1” in section keasured 2m from deck beam to the end which terminated inth ebilge. Two davits . . . were recorded as were iron pump sections, piping, 2 hawsepipes one at each end of the site, and the remains of a crushed diving helmet. This was seen concreted to what apopears to be a pump section. Ballast stones are in evidence throughout. The concretions appear very rich with 1 lead ingot 10”x5”x3” visible, 2 book presses ( one a 400mmx250mm press), copper sheathing, one piece being a wool bale stencil with the letter ‘P’ clearly visible. Iron bolts in much corroded form are also visible (c.20 x2.5mm). A diaphragm pump appears overgrown by coral close to a windlass 1.8m inlength. At a bearing of 210° from the cargo anchors and at a distance of (x) m a small boat gudgeon, fastenings, a diving helmt, wing nut and other assorted brass materials was recovered.

A site plan was produced by the Museum’s chief diver Geoff Kimpton showing the major features and the objects raised for security, conservation and diagnostic purposes. These were the crushed diving helmet, sheathing fragment, a deck light, assorted fastenings and fittings, a ballast sample, bottle, sherds, the small boat gudgeon, the stencil letter, a length of chain with 4” x 3” x ¾” links and a bottle. In examining the evidence, it was concluded that:

The wreck is that of a mid-to late 19th century vessel, iron fastened in the deadwood and keel/keelsons and part copper and brass fastened eleswhere. Iron knees and in som eplaces knee riders were also use don the construction of the vessel. The two anchors with stocks set are more an indication of vessel size than those apparently being carried as cargo. These indicate chain and fastenings sizes point to a substantial vessel of the 100-200 ton range most likely European built. The presence of the davits, small boat gudgeon, diving helmet, wool bale stencil?, lead ingot and 2 book presses are of significance and make a NW [north-west] destination or point of origin likely. Of the vessels lost in that trade only the Emma (867) nd Occator (1856) fit the size and temporal range indicated by the wreck.

With only Occator and Emma of all the known losses fitting the remains inspected and with Occator known to have been lost further north, it was concluded that this was the Emma. On the basis that it was one of the most significant of all colonial wrecks in this State, the two book presses on board were considered vital artefacts, with documents in th epossession of T.C. Sholl possibly sealed within. As a result it was recommended at the site be protected as the Emma and that a further inspection/excavation be carried out ASAP with a view to removing the book presses and other attractive material, thus avoiding their irreplaceable loss. The wreck was subsequently declared historic and a reward of $1500 shared between Dean Whiting, Serge Katarski and Jim Sellers. In September 1992 a team led by Jeremy Green and including photographer Pat Baker and diving conservators Ian Godfrey and Jon Carpenter returned to the site fixing it at 23° 05.08’S., 113°44.15’E. In finding the conditions extremely difficult in the strong seas and swell then prevailing the recommendation to recover the two presses was not acted upon (J. Carpenter, Conservation Report:14/10/1992). Additions were made to the site plan nevertheless, a number of loose items including part of a navigation instrument were raised; the site conditions were assessed and a number of objects including the presses further examined by the conservation specialists. These were found to be ‘well preserved with minimal structural damage’. A timber sample attached to a copper alloy fastening was also recovered and was later identified by Dr Godfrey as Eucalyptus species.

Though not known at the time of writing the inspection report, research subsequently conducted into the pearling and pastoral industries in the north west showed that the ‘25 tons of iron ballast’ referred to by the Resident Magistrate in his reports was in the form of the anchors and ground tackle from the New Perseverance which had been wrecked at Mystery Landing in Butcher’s Inlet just prior to the departure of the Emma from that port. Apart from stabilising the Emma the ground tackle was intended as a ‘return freight’or ‘paying ballast’ on consignment to Fremantle (R.J. Sholl, 16/8/1867, CSR 603/ 92;108). With seven anchors found on site, two (presumably Emma’s) with iron stock set and with chain ranged both along the keelson and in a chain mound, the evidence rendered the hitherto tentative identification of the Emma conclusive.

Ship Built

Owner Walter Padbury

Master Captain Badcock

Country Built UK

Port Built Lowestoft, Suffolk

Port Registered Fremantle

When Built 1859

Ship Lost

Grouped Region Mid-West

Crew 8

Deaths 42

When Lost 1867/03

Where Lost Coral Bay

Latitude -23.08255

Longitude 113.7335

Position Information GPS

Port From Cossack

Port To Fremantle

Cargo Wool, pearl, passengers

Ship Details

Engine N

Length 26.10

Beam 6.20

TONA 116.00

Draft 3.40

Museum Reference

Official Number 25291

Unique Number 178

Sunk Code Unknown

File Number 2009/0110/SG _MA-60/88

Chart Number AUS 72

Protected Protected Federal

Found Y

Inspected Y

Date Inspected 1992/09

Confidential NO