Xantho (1872/11/16)

Port Gregory

Built in 1848 as a paddle steamer by the Denny Shipbuilding Company, used by the Anstruther and Leith Steamship Company for crossings of the Firth of Forth between Leith and Aberdour. In 1860, sold and relocated to Scarborough. In July 1864, sold again, and its register transferred to Wick, from where it was permitted to take excursions to sea.

In early 1871, PS Xantho was sold to the 'metal merchant' Robert Stewart of Glasgow, who replaced the paddle engines with a second-hand Crimean War-era two-cylinder, non-condensing trunk engine built ( or assembled) in 1861 by John Penn. Stewart also lengthened the vessel's stern and fitted a propellor and a new boiler. The Crimean War type gunboat engine and those built to the same design in the ensuing years were the first high-pressure, high-revolution and mass-produced engines made for use at sea. The type also used Whitworth's Standard Thread throughout, allowing for interchangeability of parts. The refurbished, schooner-rigged SS Xantho was offered for sale in October 1871 and was purchased by Charles Edward Broadhurst, a Manchester-born entrepreneur involved in colonial ventures in north-west Australia.

Xantho was brought to Western Australia via the Suez Canal and the Straits Settlements for use by Broadhurst as a transport and mother vessel for pearling operations. Using the engine to enable it to sail into difficult harbours and against wind and tide Xantho was also effectively operated as a tramp steamer, taking whatever cargoes and passengers it could. In that role it became Western Australia's first coastal steamship. Xantho subsequently made two round trips between Fremantle, Batavia (now Jakarta), Geraldton and Broadhurst's pearling camps at Port Hedland and Banningarra (on Pardoo Station). Xantho also transported a number of northwest Aboriginal men from the Aboriginal prison at Rottnest Island back to their home near Cossack and Roebourne. In November 1879, whilst travelling down from the pearling grounds to Fremantle Xantho shipped a cargo of lead ore from Port Gregory, an outlet for the Geraldine Mine on the nearby Murchison River. Overloaded, its hull badly corroded and its deck planking opened by the tropical sun, Xantho began to take on water on the way down the coast. After returning to Port Gregory it struck a sandbar and sank.

The wreck lay forgotten until 1979 when, with the aid of local fishermen, it was located by the Maritime Archaeological Association of Western Australia, the volunteer wing of the Department of Maritime Archaeology at the Western Australian Museum. At the time iron and steam shipwrecks were effectively a new class of maritime archaeological site, requiring under the overall direction of Dr M. McCarthy a new approach in both archaeological method and conservation science commencing with a pre-disturbance survey, re-inspection and test excavation was conducted by corrosion specialists, biologists and archaeologists It found that the propulsion system and part of the stern were in a uniformly good condition, although the rest of the remains were very fragile. The study also found that the engine and other prominent parts of the wreck were unlikely to last another fifty years. Anodes were applied to the engine in order to slow down its corrosion and commence the treatment process. In April 1985, the engine was removed from the wreck site in the context of an excavation of the stern and then transported to a treatment tank at the Museum, in Fremantle. Under the direction of corrosion specialists Neil North and then Ian MacLeod, the engine was initially inundated in a solution of sodium hydroxide to prevent further corrosion, while experiments as to the most effective method of removing the 2.5 to 5 centimetres (0.98 to 2.0 in) layer of concretion from the engine iron work were performed. By March 1993, 2,500 kilograms (5,500 lb) of concretion had been removed, while 48 kilograms (110 lb) of chlorides had been extracted from the engine by electrolysis. A working model of the engine was produced by Bob Burgess using engineering drawings of the original produced by steam engineer Noel Millar. The model has allowed the Crimean War gunboat engine type, of which the Xantho engine is the only known surviving example, to be studied in operation. The engine was then disassembled under the leadership of conservator R. ( Dick Garcia) who had considerable experience in dismantling and restoring arms from WWII. As they were removed each of the engine's components were individually re-treated before it was gradually reassembled in the Museum's exhibition gallery as a 'work in progress' display. By 2006, the conservation and reconstruction was complete and the engine could be turned over by hand. A schematic showing the engine in action has also been produced and it can be viewed on the engine reconstruction section of the project website.

The archaeology of the SS Xantho

The wreck of the SS Xantho presented many anomalous features requiring explanation, as did the engine when it was excavated from its layers of concretion and then disassembled. Apart from the hull being 23 years-old and worn out, the engine was already ten years old when fitted to the former paddle-steamer, and it was found to have been running backwards to drive the ship forward. Its rotation was, as a result, contrary to the maker John Penn's requirement, resulting in increased wear. When it was disassembled by the Museum's team, loose nuts were found lying in one cylinder and repairs to the engine were found to be very rudimentary. It was also found that the pumps could not be disconnected and they ran constantly, resulting in great wear on the valve stems. They were also were situated in the stern of the ship, rendering them useless when out of trim forward as Xantho was on its final voyage. The boiler relief valve was an outdated gravity variety and not the spring type generally used at sea to avoid problems as the vessel pitched and rolled. There was no condenser for recycling the used steam back into the boiler. All this made Broadhurst's decision to purchase Xantho for use in very saline waters, on a coast where fresh water supplies were practically non-existent and where there were no engineering facilities, the nearest workshops being in Surabaya or Melbourne, difficult to understand. This in turn required an understanding of his reasons both for purchasing the vessel and the manner in which he operated the ship. This in turn led to an attempt to understand his entrepreneurial style and given his remarkable propensity for failure, his staff and his support structures. These included his family, notably his remarkably talented wife Eliza Broadhurst and their son Florance Broadhurst. One result of this archival research was a reassessment of C.E. Broadhurst, who like Xantho, had been roundly dismissed as two of Western Australia's greatest colonial-era failures. In respect of the re-evaluation of the ship itself, the research led to a realisation that its purchase, despite its age and its many deficiencies, was a bold and logical stroke typical of an entrepreneur with great vision, but lacking the necessary access to finance and logistical support. Being mass-produced, for example, spare parts were readily available (a spare connecting-rod was found in the ship's engine room) and being very simple, easily-accessible and compact, repairs could be effected with only a rudimentary knowledge of marine engineering. On reflection it became apparent that Broadhurst also used Xantho primarily as a sailing ship and would not have used the ship's engine other than to assist him proceed when the wind was against him, especially when entering the often difficult tidal harbours on the north-west coast. Further, with an eye to obtaining the lucrative subsidy for operating a steamer to schedule on the coast, Broadhurst also appears to have made a point by steaming into port and thereby impressing a colonial administration crying out for steam transport on the coast. The Museum's exhibition on the SS Xantho is entitled 'Steamships to Suffragettes' focussing as much on the people involved (including the Broadhurst's suffragette daughter Katherine) as it does on the engine and its conservation.

Indigenous Depictions

Xantho impacted both visually and socially on indigenous groups like the Jaburrara, Martuthunira, and Ngarluma people, who lived in the hinterland of Nickol Bay. Although no European illustrations of the ship exist, there are several examples of Aboriginal rock carvings at Inthanoona Station inland from Cossack identified as the SS Xantho. Rock art at Walga Rock is also believed to be depicting the vessel.

Ship Built

Owner Charles Edward Broadhurst

Master Captain Denicke

Builder William Denny and Company

Country Built Scotland

Port Built Dumbarton

When Built 1848

Ship Lost

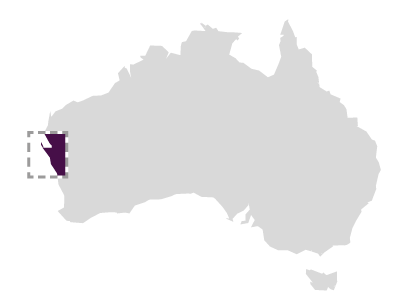

Grouped Region Mid-West

Crew 20

When Lost 1872/11/16

Where Lost Port Gregory

Latitude -28.1865266667

Longitude 114.236225

Position Information Obtained from aerial photograph DoLA 2004

Port From Port Gregory

Port To Fremantle

Cargo Lead ore

Ship Details

Engine TR2 64 HP, first Paddle Steamer

Length 34.70

Beam 5.40

TONA 6144.00

Draft 2.60

Museum Reference

Official Number 7802

Unique Number 799

Sunk Code Foundered

File Number 2009/0216/SG _MA-9/79

Chart Number AUS 741

Protected Protected Federal

Found Y

Inspected Y

Date Inspected 2003/10

Confidential NO