Pet (1882/03/01)

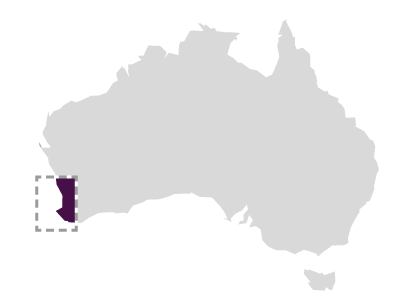

80km SE of Cape Leeuwin

Pet, a single-decked 2-masted topsail schooner with an oval counter stern and a good sheer, was built by Robert Wrightson at Fremantle, and launched in February 1877. It had a small deckhouse at the break of the poop and a short forecastle deck. Wrightson’s yard, where he commenced operations in 1867, was on the beach between South Jetty and the mouth of the tunnel under the Roundhouse, and not far from the Commissariat building (Dickson, 1998). He initially maintained ownership of the schooner, but in June 1878 he sold 32 shares each to Alexander Joseph McRae and William Dalgety Moore. The vessel was under charter to Maurice Coleman Davies, who had a timber lease near Collie and had built two small mills at Worsley, transporting the timber to Bunbury by bullock cart. The Pet was deeply laden with a cargo of 120 tonnes of green tuart timber when it sailed at 6.30 a.m. on Wednesday 1 March 1882, under the command of Peter Littlejohn, with a crew of six. In his evidence to the subsequent inquiry the mate, William Henrietta, stated that ‘the vessel was very deep, I consider deeper laden than I like to see. She showed nineteen or twenty inches from her covering board to the water’ (quoted in Dixon, 2009a). The Pet was insured for £1 200.

THE LOSS

During the afternoon of Saturday 4 March 1882 a large sperm whale was seen, and within minutes it attacked the Pet, stoving in a large section of the starboard bow. The vessel began to sink and the crew, except the master, mate and one crewman, took to the boats. Captain Littlejohn is variously described as either being stunned by the incident and unable to comprehend his predicament (Cairns & Henderson, 1995), or that he went below to retrieve his navigation instruments and ship’s papers (Dickson, 1998). The contemporary newspaper reports and evidence given at the subsequent inquiry indicate that the captain was on deck at the time the Pet sank. Certainly he went down with the schooner, while the mate and the crewman only escaped a similar fate by diving off the stern at the last minute. The vessel sank only three minutes after being struck. After waiting unsuccessfully to see if Captain Littlejohn’s body would come to the surface, the mate and the crew made for Hamelin Bay which they reached about 2.30 p.m. the following day, having rowed for 22 hours.

A report by the crew states:

When about 50 miles to the south-west of Cape Leeuwin a large sperm whale was sighted in the distance off the starboard quarter. At first the monster did not attract a great amount of attention, but something must have occurred to enrage the beast as it suddenly charged the ship in the most determined manner. So suddenly was the onslaught made that there was no time to take steps to evade or repel the attack. The whale struck on the starboard bow, knocking a large hole in her through which the water poured with great rapidity. Captain Littlejohn was drowned and the crew, W. Henrietta, mate; W. Bull, G. Moore, H. Green, W. Waldon and B. Nelson made it to safety (quoted in Dickson, 1996).

INQUIRY

The subsequent Court of Inquiry held at Busselton before Joseph Strelley Harris, acting subcollector of Customs, and Dr Charles Smith Bompass, J.P., on 13 March 1882 attached no blame for the loss on the captain, finding that the Pet had been rammed and sunk by a large sperm whale. It was noted that Captain Littlejohn had not attempted to save himself. The mate stated in his evidence that he was below decks when at about 4.25 p.m. he heard the man at the wheel cry out that there was a whale close to the Pet:

I ran on deck and saw the wake of the whale about ten fathoms on our starboard bow. I intended to go forward and before I reached the end of the poop, he struck us. I knew by the crash of the timber some serious damage had occurred to the vessel.

I gave orders to sound the pumps, all the men were on deck with the exception of the captain. I saw the whale lying alongside the vessel apparently stunned, also pieces of planking belonging to the vessel floating about. I gave orders to cut the lashings of the boat. We had two boats on the main hatch. I went forward to inspect the damage and found the whole of the starboard bow from the cat-head to the starboard fore rigging was stove in and the water rushing in.

I immediately ran aft and said ‘never mind the pumps, we must get the boat over the side’. I assisted to get them over, while doing so the captain came out of his cabin, which was a house on deck and asked what all the noise was about. I replied, ‘we have been struck by a whale and are foundering.’ He disbelieved it so I requested him to look for himself. The bowsprit and windlass being under water at this time. We had been going at the rate of 6 knots.

The captain appeared stupefied. We launched the boat, all the crew were present helping, we put oars into the boat. I instructed the four men who were in her to get clear of the vessel. I threw several more oars overboard. About this time the water was a foot over the main hatch. One of the men called out I have got the rowlocks. I then jumped onto the poop. The captain had hold of a lifeline and was looking forward at the vessel going down.

I called to him. ‘You had better jump into the boat,’ but he made no answer whereupon I again asked him to jump. But he turned slowly round, and staring aft, said vaguely, ‘Bring the boat here.’ I then called to the cook to bring the boat alongside to enable the captain to get in, but the men in the boat said, ‘No, we shall be drawn down by the sinking vessel.’ I walked aft and got out on the stern.

Her rudder and about 8 or 10 feet of the keel was out of the water at this time, looking forward her fore topsail had taken aback as she was going down and broke off at the fore topmast—short of the cap. I dived right astern as far as I could from the vessel—Green also did the same. When I got to the surface the vessel had disappeared.

I did not see the Captain after speaking to him. We were out of sight of land and according to my reckoning about 50 miles SW of Cape Leeuwin. The vessel foundered about 4.30 p.m.. We remained at the spot for some time amongst the wreckage which continually came up, looking for the Captain. We took two sheep into the boat.

I was aware that the course to be steered was NE and I steered that course by the moon as nearly as I could. We sighted land at daylight, Cape Leeuwin and I think we were quite 20 miles away. I told the men I would make for Port Hamelin where we arrived about 2.30 p.m. on Sunday. There was a very nasty sea running all night and rain squalls from the SW, the wind favourable for us.

I should say the whale was 60 or 70 feet long, the largest whale I have seen of the sort, and we had seen no sign of whales before this one (quoted in Dickson, 2009).

Ship Built

Owner A. J. McRae and W.D. Moore

Master Captain Peter Littlejohn

Builder Robert Wrightson

Country Built WA

Port Built Fremantle

Port Registered Fremantle

When Built 1876

Ship Lost

Grouped Region South-West-Coast

Sinking Hit whale, holed

Deaths 1

When Lost 1882/03/01

Where Lost 80km SE of Cape Leeuwin

Port From Bunbury

Port To Adelaide

Cargo Timber

Ship Details

Engine N

Length 26.10

Beam 5.90

TONA 89.92

TONB 84.84

Draft 2.50

Museum Reference

Official Number 75293

Unique Number 345

Registration Number 2/1877

Sunk Code Wrecked and sunk

Chart Number 1034

Protected Protected Federal

Found N

Inspected N

Confidential NO