• The Baudin Expedition • French maps of Australia • Australian flora and fauna presented in France

Early French interest

in the southland

The roots of the voyage of the French corvette L’Uranie

in 1817-1820 date back to Paulmier de Gonneville in

1504. He thought, after experiencing a violent storm

near the Cape of Good Hope, that he had chanced

on the fabled Terra Australis Incognita, a vast southern

land mass long postulated as a necessary balance to

the continents in the northern hemisphere. Thereafter

called ‘Gonneville Land’ by the French, it became a

focus for their maritime aspirations in the region and in

1738 Bouvet de Lozier set out in search of it but found

only the barren island that now bears his name.

By then the Dutch, notably Dirk Hartog (1616), Carstensz

(1623), Thijssen (1627), Abel Tasman (1642 & 1644)

and Willem de Vlamingh (1697) had landed and charted

much of the north, west and south coasts of what

afterwards became known as New Holland. William

Dampier also had a hand in the exploration of New

Holland and he records landing on the north west coast

in 1688/1699. Though following the Dutch in dismissing the

land and its inhabitants in a hugely popular and widely

disseminated account—and thereby fixing the negative

attitudes that were to remain commonly held for another

century—he and his colleagues were the first Britons

to land there.

A French chart of New Holland circa 1850.

The loss of territory to the British on the north American

continent in the late 1750s caused the French to actively

look elsewhere for colonies. In 1763 Louis Antoine de

Bougainville, who had fought against the British in Canada

and who was the first Frenchman to sail around the world,

established a small colony at Port Louis on what he called

the Iles Malouines in honour of the predominantly St Malo

element amongst his colonists.

The British countered this in 1764 by sending Commodore

John Byron who arrived early in the following year, took

possession of them as the Falkland Islands.

In 1767 France ceded its rights to Spain, commencing a

| chain of events that has led to Argentina claiming the

islands as Las Islas Malvinas.

It was a disagreement that has had repercussions well

into the modern day, and is one that also had ramifications

for the Uranie voyage and for the survival of its castaways.

In commenting on his visit to the area in 1820, the Antarctic

explorer James Weddell stated that the colonists were

an …industrious

and enterprising people, after having made

considerable progress in fertilising the ground, were displaced

by the Spaniards, who claimed the islands.

They, however, partly through political motives…neglected

the improvement of the country, and latterly entirely

abandoned it (Weddell, 1827:94)

Continuing what in effect was a ‘superpower’ race for

territory, in 1766 the British navy sent two ships under

Wallis and Carteret to the south Pacific in search of the

fabled southern continent, and the French despatched

Bougainville with the same intention just three months

later.

While the French and the British found many islands in

the Pacific, including Tahiti and Pitcairn, neither found

the southern continent.

The closest Bougainville came to Terra Australis was

when he encountered the Great Barrier Reef adjacent

to present-day Cooktown in far north Queensland.

On his return home in 1769 Bougainville published an

account entitled A Voyage Round The World, that

increased French interest in the Pacific.

In the interim James Cook departed on a scientific voyage

with secret instructions to explore the south Pacific.

In completing his first exploration in the period 1768-1771,

Cook called at Tahiti, circumnavigated New Zealand and

then travelled along a vast land mass he claimed for Britain

and named New South Wales. His proclamation was effected

with little reference, as was the fashion throughout the world

in those times, for the indigenous peoples and their rights.

This left unexplored the eastern part of the south coast,

lying between New Holland and Cook’s New South Wales,

and there existed a belief that a vast strait passed between

New Holland and New South Wales. (Scott, 1914:53).

The annexation of New Holland for France.

In 1771, two expeditions left Ile de France for the Indian

Ocean in search of Gonneville’s Land. One, led by Marion

Dufresne, sailed to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) and

as far as New Zealand, alerting France to their worth though

as the names suggest both had been earlier discovered

by the Dutch, in this case by Abel Tasman.

The other, a two-ship expedition was led by Y.J. de

Kerguelen and it included as second in command, François

de Saint Aloüarn The ships separated and Kerguelen,

upon discovering what he thought to be Gonneville’s Land,

hurried home to announce the discovery of what he called

France Australe. Later, it proved to be a barren island that

now bears his name. In the meantime St Aloüarn in Le Gros

Ventre continued the search for Gonneville’s Land.

Unsuccessful, he then made for the coast of New Holland,

and in landing on Dirk Hartog Island at Dampier’s Shark Bay,

Saint Aloüarn annexed the coast for France in March 1772,

Godard and de Kerros, 2002; Marchant, 1998, McCarthy,

1998).

The La Pérouse and d’Entrecasteaux Expeditions

The young Napoleon Bonaparte applied for a place on the

next French expedition to the region under the command

of J.F. Galaup, comte de la Pérouse, but was lucky to be

refused. The best equipped of all scientific forays, this

two-ship expedition left French shores with a large contingent

of scientists and naval personnel in 1785. After extensive

explorations in the Pacific, they were ordered from

Kamchatka to Botany Bay in New South South Wales in

order to observe the British landing there in 1788 (Wood,

1922:507).

After doing so they departed for further work in the South

Seas and were never seen again.

In this same period William Bligh was in these waters with

HMS Bounty, following on from Dampier’s earlier revelations

about the efficacies of breadfruit. After the infamous mutiny,

Bligh was not to know that the Australian first fleet had

landed successfully under the curious eyes of the French,

and navigated in an open boat across the top of the

continent to Timor and safety.

In September 1791 another well-equipped French

expedition was sent under the command of J.A.Bruni

d’Entrecasteux with Le Recherche and L’Espérance to

continue the exploration and to search for La Pérouse.

Amongst the complement were scientists, botanists, a

gardener and hydrographers. On the south coast of

New Holland, they took many natural science specimens,

charted great skill and named many features.

While

they were to continue to give generally adverse

accounts of New Holland, at Tasmania their descriptions

of the land and people were to provide some relief to

the predominantly negative reports of previous explorers.

There d’Entrecasteaux observed that the tribe they

encountered

…seems

to offer the most perfect image of pristine society, in

which men have not yet been stirred by passions, or corrupted

by the vices caused by civilization…Oh! How much would those

civilized people who boast about the extent of their knowledge,

learn from this school of nature

(Duyker & Duyker, 2001 :xxxviii).

Their visit followed that of George Vancouver, who left

Plymouth in April 1791 for the north Pacific via the Indian

Ocean and the south Pacific. He landed at, and named

King George the Third Sound (Albany), then travelled for

a short distance along the southern coast before being

forced off it by bad weather.

In 1793 the d’Entrecasteaux expedition landed in the

East Indies on its way home to news of the execution of

King Louis XVI and a state of war between the new

Republic and much of Europe. By then both commanders,

d’Entrecasteaux, and his second-in-command, Huon de

Kermadec, and many others had perished through illness.

To make matters worse, the republicans on board were

denounced by their shipmates, imprisoned by the Dutch,

and both ships were sold to defray expenses. After being

confiscated by the British, the extensive natural science

collections, maps and charts eventually found their way

back to France where the botanist J.J.H. de Labillardière’s

Relation du Voyage à la Recherche de La Pérouse was

published in 1799, going through three English editions

and two German by 1804.

Containing 265 black and white illustrations together

with 13 plates by the renowned botanical artist P.J.

Redouté, it was the first illustrated work after Dampier’s

account of his voyage to New Holland in 1699 to

capture the imagination of the Europeans in respect

of the flora and fauna of the Southland. The expedition’s

hydrographer Beautemps-Beaupré then published his

atlas in 1807 and his cartographic works were roundly

praised (Duyker and Duyker, 2001).

The Baudin expedition

In 1800, with the approval of Napoleon, then First Consul,

yet another two-ship expedition left France led by Nicolas

Baudin. The two ships employed were Le Géographe under

Baudin and Le Naturaliste under J.F.E. Hamelin. They had

orders to continue the exploration of the Southland and were

also required to examine the question whether the strait

thought to lie between the ‘two great and nearly equal islands’

of New Holland and New South Wales did exist

(Scott, 1914:530).

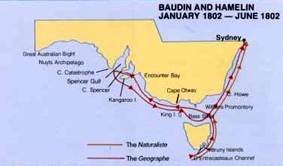

A map showing part of the Baudin explorations on the

south and east coast of New Holland (from Jacob and

Vellios, 1987)

Though the charts of the d’Entrecasteaux expedition had

yet to be published, Baudin was provided with preliminary

engravings. The enterprise was also mightily hampered by

having a microcosm of a fractured French society and in

having many civilian scientists on board.

Though many left the expedition in Mauritius, and returned

home intent on poisoning Baudin’s reputation, the

explorations, which were conducted between 1801 through

to 1803 resulted in many useful discoveries and

anthropological observations, in important chart and map

making, and in securing a vast number of natural science

specimens. Despite these successes, it has taken a full

two hundred years for Baudin to be favourably reassessed.

.Louis de

Freycinet and the de Vlamingh plate

On board Le Naturaliste was Sub-Lt Louis Freycinet.

While the ship was at Shark Bay he was sent by boat

to conduct surveys of the area—work that he later

continued while in command of Le Casuarina and later

in L’Uranie.

He also appears to have been on board when the ship’s chief

helmsman returned with an ancient inscribed pewter plate

commemorating the landing of the Dutch explorer Willem de

Vlamingh at Shark Bay in 1697. Having long-since fallen from its

post, it had been accidently found lying half buried in the sand

at the top of a prominent point overlooking the entrance to the

bay

.

.

The discovery was of great historical significance, for on finding

a similar plate deposited by Dirk Hartog in 1616, Vlamingh had

the original inscription copied onto a new plate to which he

appended an account of his own visit before erecting it at the

same spot (Playford, 1998). He then sailed away with the

original, beginning a chain of events that was later to include

the visit of L’Uranie. Though the Naturaliste men found the

Vlamingh plate lying in the sand, where it had fallen from the

post, they recognised its importance and immediately brought

it back for Hamelin to examine.

In objecting to the notion that the plate be removed to France,

and in considering that to do otherwise would have been

historical ‘vandalism’ (Marchant, 1998:176; Halls, 1974),

Hamelin had Vlamingh’s plate and a plate of his own re-erected

on new posts, the first at the Dutch explorer’s site and the

second at an as yet undetermined location.

Freycinet apparently did not approve of this precursor to modern

museological thinking, and felt that it should have been removed

for safekeeping in France, but was too junior to prevent the

return of the relic to its original site. In recognising the importance

of the site, Freycinet’s chart of the region refers to the site as

Cap de L’Inscription (Cape Inscription).

As unequivocal evidence of the prior landing of Europeans on

their shores, the Hartog, Vlamingh and the Hamelin plates are

relics of immense significance to Australians generally, and it

has been said by one historian that:

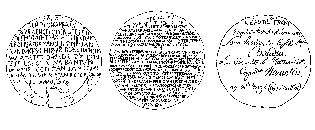

The

title deeds, so to speak, attesting European discovery of Western

Australia are three pewter plates left at Cape Inscription, Shark Bay,

on three separate occasion (Halls, 1974). L to R; Hartog

1616,

de Vlamingh 1697 and Hamelin 1803.

Go

to the Uranie voyages