Relics: Tell tale signs of the last hours of the Roebuck voyage

The location of the wrecksite

In brief the sequence of events leading to the location of relics that

have since proved an indisputable pointer to the location of William Dampier’s

ship are:

On the morning of 15 March, 2001, the day after arrival on the Island,

the Museum team proceeded in the RAF fishing/diving boat Ascension Frigate

skippered by our liaison officer Flt Lt Richard Burke RAF for a familiarization

dive of the waters in the region.

There an indication was had of the sea conditions, of the underwater terrain,

of the fish life and (very importantly) of the appearance of wreckage

and other detritus in Ascension Island waters. This was essential, for

initially (and quite incorrectly) the team had expected substantial coral

growth over wreckage, as was common in the Indo-Pacific region.

Later in the day the group then sailed to the position recorded by Wm.

Dampier on 24 February 1701 (Julian Calendar), while his ship was in a

sinking state. Winds were offshore, seas were slight, on a low swell.

Dampier’s anchorage, looking towards the shore with the

Island’s

Tanker, the Maersk Gannet.

Journals and the other accounts of the loss of the ship were read to those

onboard while Ascension Frigate was stationed as close as possible at

Roebuck’s first anchorage in 10 fathoms of water. An exact replication

of the positions given by Dampier i.e.

‘…

in ten fathom and half water, sandy ground about half a mile from the

shoare, the S. point of the bay bore S.S.W. dist. one mile and a half

and the northernmost point, N.E.1/2 N.dist. two mile…’

was not possible, it being occupied on the occasion of our visit

by the Island’s Tanker, the Maersk Gannet.

While there pondering the situation and with an offshore (predominantly

easterly) wind, a small ‘willy-willy’ (circular localised wind

gust) was seen on shore heralding the temporary change of wind direction

that is customary around midday. This had been predicted by our guide

Richard Burke, as a regular, but short-lived daily phenomenon. On this

occasion it translated into a rare sustained sea-breeze as per the events

that befell Dampier 300 years ago.

With these fortuitous events the team were able to deduce with an element

of surety Dampier’s next course of action in the minutes that would

have elapsed as he recognised the opportunity and ordered his men to the

windlass and aloft. Then with time running out as the anchor was raised

and the sails were unfurled and filled, there was just enough of the breeze

remaining to allow him to run into 7 fathoms where the breeze then died.

He then sent an anchor ashore in order to warp the ship in close.

Thus we were able to settle on the probable grounding site of HM Ship

Roebuck. When quizzed on their choice of action in the circumstances,

for example, six of the seven on board Ascension Frigate chose a direct

easterly route into the beach, with one selecting a south easterly course

in towards the beach at what is now the pier. The winds certainly allowed

for such a range of choices, even for a cumbersome and water-laden ‘square

rigger’ such as the sinking Roebuck. Being closest and clear of any

visible obstructions, the middle-to-northern end of Long Beach was deemed

the best starting place for the search by the majority, though it needs

be admitted that it was a near-unanimous choice that was partly dictated

choice by the heavy swells which seemed lower in that area.

At the evening meeting, experience at wrecks driven ashore in storms or

similar circumstances was drawn on to form a predictive model for the

ensuing search. One very useful example was the VOC ship

Zuytdorp (1712) a much larger vessel than Roebuck and one drawing

c.4-5 metres, which came to rest lying in 2-3 metres of extremely rough

water on the Western Australian coast. Another was the French exploration

Frigate L’Uranie (1820) of slightly

less draught, that the team had found and inspected in 3-4 metres of much

less turbulent water at the Falkland Islands the previous week.

These two examples indicated that, if it had not been blown back out to

sea, Dampier’s wreck most likely lay in much less than the 21 feet

of water (3 and a half fathoms) described by Dampier as the grounding

site. This depth and the area to seaward of it was the object of past

sea-based searches in 1979 and 1985.

As a result Western Australian Museum search was to be focussed in the

shallows inshore of that depth, close by shore and right in the breakers

and, if unsuccessful, it was intended to commence a series of water-drive

probes onshore on the beach itself. The first stages of the search were

to be conducted from land through the waves utilising a common, very simple,

but quite accurate ‘transit’ survey method. This entailed swimming

out from the beach along a line marked onshore with temporary ‘navigation

leads’ similar to those used by vessels to navigate in and out of

narrow channels. At the completion of that line the divers were to move

down to the next line 5metres south and then swim back to the shore.

The Transit Search method

The next morning,

on March 16, the team then proceeded to the northern end of Clarence Bay

by land to commence the search of Long Beach. The first two sets of ‘leads’

were erected and two divers (Geoff Kimpton andJohn Lashmar) commenced

work. While they were occupied in this manner the others in the team were

engaged erecting the next pair of ‘leads’ for the divers to

use as their navigational guide. A search of the beach and of the rocks

in the wave line was also conducted.

The location of wreckage

Again fortuitously, the beach was found to be heavily eroded and very

steep just inshore of high water mark, with rocks, formerly covered with

sand at the northern end completely exposed.

Erosion at the beach with Hugh Edwards and detritus,

Many heavily-concreted

iron fastenings were seen amongst the rocks at the north end of the bay.

Though clearly of ancient origin given their form, these were interspersed

with such large quantities of modern concreted, iron and steel detritus,

that it precluded any definitive conclusions being made, for the area

was clearly a natural wreckage trap.

In searching along the first 8 transit lines (0-45m) in a moderate swell

and smooth seas from the shore to depths offshore of around 7-8 metres

deep (the practical limit of the visibility) and no more than 200 metres

from the beach, Kimpton and Lashmar saw numerous concreted objects and

debris. It soon became apparent from an examination of the recently exposed

beach that its entire northern end was littered above and below water

with steel drums (appearing as iron hoops), jetty fittings, wreckage and

rubbish. Significant or interesting items requiring further inspection

were marked from shore, again using a series of intersecting transit markers.

Amongst the rocks at the northern end of the beach was a considerable

amount of material, consisting of concreted iron work, modern detritus,

ceramic fragments, and what appeared to be a broken ceramic amulet, similar

to those seen by the author on the ‘Blackbirder’ Foam (1893

) on the Great Barrier Reef. The find was inconclusive, however and in

not being proceeded with, was left in-situ.

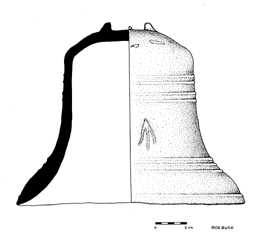

Above & below: The Bell wedged in the rocks. Photo John Lashmar

After just under an

hour of searching with Geoff Kimpton along the transit lines set on the

beach,John Lashmar descended and while swimming along the bottom he located

a bronze bell on the 9th transit line. It was found lying almost totally

uncovered but affixed to a cleft in rocks c. 90m from shore on a rock/sand

seabed c. 4m deep. Indications were that it had only recently been exposed—with

a distinct line on its surface delineating the high point of the latest

sand movement around it. The search regime was then halted, with the team

uniformly in disbelief.

After the find was examined by all present on snorkel the search was suspended

for the day while the bell was recorded with video and still cameras on

SCUBA. While thus engaged numerous iron concretions, some lead? Sheating,

crumpled iron work and large quantities of clearly modern detritus were

seen in the vicinity of the bell, including many 44 gallon drum ends,

and a buried tractor tyre with only a small part of is side casing visible.

This provided a very useful clue to the depth of the sand in the area

surrounding the bell find.

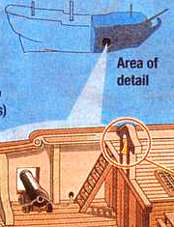

The Bell and Belfry in situ on the Roebuck

For a while the ordered progression of the search was lost and a random

swim of the immediate area was conducted. A short time later a heavily-concreted

longboat grapnel was found concreted to a rock on an exposed rocky seabed.

Then a large clam was found exposed in a cleft in the reef on the seabed.

It lay in the swell in shallower water c. 100 metres south of the bell

to the south and c. 8 metres from shore. The grapnel lay closer to the

bell in slightly deeper water than the clam.

The Grapnel concreted to the

rocks

Further south in shallow

water close to the beach and in a very turbulent location, a slightly

tapering iron object similar to the heavily eroded cannon found on the

wreck of the VOC Ship Zuytdorp (1712), again in the wave line and firmly

wedged amongst the rocks. Once a tapering cylinder, the object had its

upper surface worn away with sandblasting in the surge. Trunnions or,

as is often the case in turbulent exposed conditions, stubs of trunnions,

were not visible, precluding any identification of it as a cannon.

It also had some of the characteristics of an iron bilge pump pipe, (whose

discrete lengths are often incorrectly reported as cannon), again no identification

was made. In this case measurements could not be taken that would have

resolved these issues. Throughout there were also landing craft/airstrip

tracks, 44 gallon drum ends, and other unidentified modern detritus, including

various sizes and diameters of modern pipe, which though they had no discernible

taper were ubiquitous enough to preclude any conclusive identification

of the object seen.

The dive was then concluded and the evidence reviewed. This led to

the decision to raise the Bell and Clam as shown below.

Mike McCarthy brings up the bell, note the bells superb condition

after being covered by sand for centuries.

John Williams inspects the Clam after it was

removed from the rocks.

Above: Geoff Kimpton's sketch made of the bell following

its discovery

Above: A Broadarrow in detail from a contemporary wreck

Blelow: TheMuseum team on the beach with the clam and bell