Bertram

and Klausmann’s 'Atlantis' Seaplane Float

By Dr Michael

(Mack) McCarthy. A

precis of a story first presented by Scott Sledge, then of the WA Maritime

Museum.

• Flight into hell • Rescue

• Recovery • Conservation

• Back to Projects

Flight Into Hell

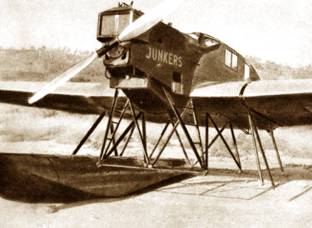

At midnight on 14/15 May 1932, German aviators

Hans Bertram and Adolph Klausmann set of from

Timor in an open cockpit Junkers seaplane (model

JU W-33), named Atlantis, in order to make the first

night flight to Australia.

A signed photograph of Hans Bertram circa 1982, as sent

to aviation historian Merv Prime. Photo courtesy Merv Prime

Darwin was an estimated 250 miles and seven

hours flying time away and in their estimate, the

fuel supply would be more than sufficient.

Counting on breakfast at Darwin, they carried no

food or water. They became disoriented during a

violent storm over the Timor Sea and force-landed

out of fuel on the desolate Kimberley coast the

next day.

During ten days of intensive searching rescue

parties concentrating in the Darwin area failed to

locate any trace of the missing aircraft and the

official searches were reluctantly called off.

Top; The Junkers JU W-33 Atlantis, equiped with

conventional undercarriage, in a rare air-to-air

photographic portrait. Above: the replica built for the

documentary film.

Hundreds of miles to the west, totally lost, the German aviators, became desperate for lack of food and water,

removed a float from their seaplane and attempted to sail to safety. The improvised sail and rudder proved

un-manageable in high winds and strong offshore current. After five gruelling days and nights paddling the

lost aviators struggled back to shore, having failed to attract the notice of a coastal steam ship which passed

within a few hundred metres of their makeshift boat. To add to their woes, the bow had been dashed against

sharp rocks and virtually destroyed.

Top left: The makeshift canoe and mast and the real Junkers JU W-33

Atlantis minus its float (right and lower).

Several attempts were made to walk out overland, but found no human habitation in what seemed a limitless

expanse of inhospitable bushland. They then made a final effort to save themselves using the stern half of

the float as a canoe. This tiny boat was no use on the open sea.

Rescue - Top

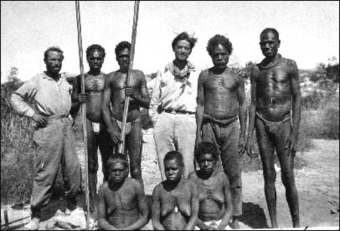

Starved and exhausted, the aviators finally gave up hope and were very near death when they were

discovered by an Aboriginal search party from Drysdale River Mission (now called Kalum-buru, just west of

the town of Wyndham). The Germans had been almost entirely without food for 40 days. Klausmann had

become un-hinged mentally and Bertram had lost several teeth. Both were so weak from starvation that they

could only swaliow after their Aboriginal saviours had chewed tood for them.

Klausmann and Bertram with their Aboriginal rescuers

It took 12 more days before rescue parties could get the pitifully weak men to Wyndham. Bertram regained his

health in Perth, and eventually reclaimed the Atlantis from the Kimberley coast, using a float borrowed from

another seaplane.

Throughout their ordeal the two made a photographic record that has survived to this day and after Bertram

arrived back in Germany with Atlantis, he wrote a book saying,

We were found by natives of Australia, naked, black men. Those Samaritans ot the wilds

tended and cared for us. Their treatment of us showed a generosity that I have rarely met

with in any people in the world. In order to thank the Aborigines of Australia I am writing

this account.

Later, two other books were published, one an english-language reprint of Bertram’s original Flug in die Holle

(Flight into Hell) and the other, published in 1979 enititled Atlantis is Missing.

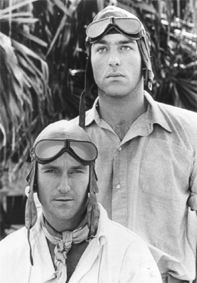

The story was adapted for television by the ABC and screened in 1985. Three years later another

expedition to the area led by Scott Sledge followed the footsteps of the aviators and later, with

the assistance of the RAN, succeeded in recovering a large missing section of the float. This was

presented to the museum in 1988.

The float as found, half buried (left) and the research team uncovering the float (right)

The epic run of one of the Aboriginal men Andumeri, who, on finding them ran an extrodinary marathon

and swam crocodile infested rivers to advise the authorities that the flyers had been found has been

immortalised in a website, musical play and CD of songs commemorating all who landed on the Western

Australian shores in a destitute condition, starting with those lost from the Eastindiaman wrecks that litter the

West Australian Coast. The website, play and CD are all aptly entitled Strangers on the Shore and were

all produced by Lesley Silvester (check) and Michael Murray.

Above: The replica Junkers built for the documentray film, seen here at Broome.

ABC/Merv Prime. Below: The two actors depicting Bertram and Klausmann.

Recovery Top

The battered, sawn-off seaplane float remained abandoned and lost until spotted by a WA Maritime Museum

team 46 years later. In October 1979, Scott Sledge, then the Inspector of Wrecks, accompanied the RAN

patrol boat HMAS Assail to excavate the retrieve the float which was badly corroded from exposure to salt

and the extreme humidity variations of a harsh climate.

The removal of the float to the HMAS Assai (left) and (right) part of Western Australia's vast and desolate 'top end' .

Conservation and Restoration - Top

Close inspection showed that much of the skin and many of the structural members had been completely

destroyed by corrosion and that their shape was only kept by a cemented mixture of oxidized metal and the

local brown clay and sand. Copper from the original Duralumin had redeposited on parts of the sound metal

and this had caused massive pitting.

David Gilroy of the Museum's Conservation Laboratory at work (left) and as currently displayed (right).

The fioat was acting like a short-circuited battery and if left untreated it would have been completely destroyed.

Dr lan MacLeod of the Museum's Conservation Laboratory developed a new treatment method to stabilize the

corroding float. (See Technical Section).

Early in 1982 David Gilroy of the Museum's Conservation Laboratory undertook to shore up the fragile artefact

so that it could go on public display. Flexible perspex was fitted to restore the shape of the perished end Finally,

the loose pieces of metal were painstakingly refitted so that as much of the original float as possible could be dispiayed.

Above left: The Junkers film replica in the RAAF Museum at Bull Creek in Perth.

Right: A replica of the float on display at the Broome Historical Museum today.

Click here to go to the Atlantis website story 'Stangers on the Shore'

by Lesley Silvester and Mike Murray.

Top