Pseudoscorpions of the World has been developed to provide some basic information on the world of pseudoscorpions and, in particular, provide information about the various pseudoscorpion families, valid names of genera and species, and a comprehensive list of the scientific literature that deal with pseudoscorpions.

What are pseudoscorpions?

Pseudoscorpions are small arachnids that bear a pair of chelate pedipalps, a pair of two-segmented chelicerae, four pairs of legs, and an ovate abdomen. They superficially resemble small scorpions but they lack the elongate tail (metasoma) and sting.

They are considered to be most similar to sun-spiders (Solifugae) as both groups share numerous features in common, such as an elongated femur-like patella on all legs, coxae that meet in the mid-line, two-segmented chelicerae, paired tracheal stigmata opening on opisthosomal sclerites 3 and 4, and the apotele of each leg with a soft empodium or pulvillus (termed an arolium in pseudoscorpions). These two orders represent the only members of the Haplocnemata.

Pseudoscorpions transfer sperm in packages attached to a spermatophore, which is produced from the male’s gonopore and attached to the substrate. Males of most families that have been studied (Chthoniidae, Tridenchthoniidae, Pseudogarypidae, Neobisiidae, Garypidae, Larcidae, Geogarypidae, Olpiidae and Cheiridiidae) simply deposit a spermatophore without any courtship or even in the presence of a female. The females somehow find the spermatophore and draw the sperm packet into the gonopore. Males of Serianus (Garypinidae) deposit a spermatophore in the presence of a female, but there is no physical contact between the pair. Members of the Cheliferoidea (Atemnidae, Cheliferidae, Chernetidae and Withiidae) perform an elaborate mating dance in which males actively court females, touching and posturing the females, culminating in grasping the female with his pedipalps, depositing a spermatophore on the substrate. He then assists the female to move over the spermatophore, and she then draws the sperm packet into her gonopore.

The eggs mature internally and the embryos are deposited into a brood-sac attached to the gonopore. The embryos mature until the protonymphs emerge from the brood-sac. They remain with the female for a short time and eventually disperse for a solitary existence.

There are four post-embryonic stages, protonymph, deutonymph, tritonymph and adult. The nymphal stages are generally free-living although the protonymphs of some species are immobile. The adults do not moult any further.

Many pseudoscorpions build a small silken chamber in which to moult, develop their brood-sac, or shelter from hazardous environmental conditions. The silk discharges from a tube (the galea) situated at the end of the movable cheliceral finger. The silk glands are situated in the cephalothorax.

All pseudoscorpions of the suborder Iocheirata possess venom glands within one or both of their chelal fingers. The active components of the venom are unknown.

Many pseudoscorpions have been found association with other animals. Some are obligate commensals spending their entire life cycle in the nests or fur of mammals (e.g. many species of Lasiochernes and Megachernes). Others form associations with flying insects, attaching themselves to legs, other body parts or, sometimes, under the elytra of beetles.

Phylogeny

Scheme of classification - Chamberlin (1931)

Very few phylogenetic hypotheses have been proposed in the scientific literature. Chamberlin (1931) depicted a “scheme of classification” which was modeled on the classification that he proposed in the monograph. Some rearrangements were proposed by later authors, including the addition and deletion of families, but the overall scheme remained essentially the same.

- The scheme of classification proposed by Chamberlin 1931

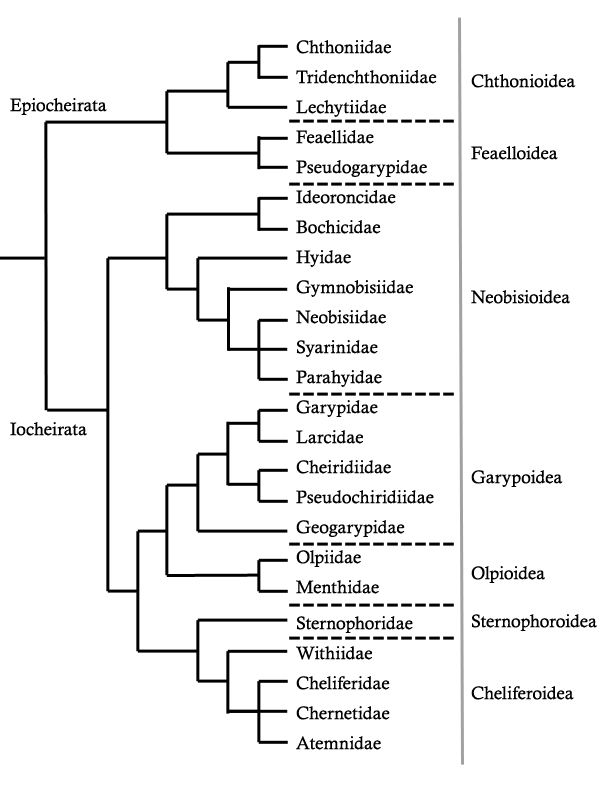

Phylogenetic hypothesis - Harvey (1992)

Harvey (1992) presented a phylogenetic hypothesis based upon a cladistic analysis of 126 characters. This tree (reproduced below) proposed a number of significant changes:

- The Feaelloidea was thought to represent the sister-group to the Chthonioidea, which were united in the suborder Epiocheirata (meaning gentle hand, and referring to the lack of a venom apparatus in the chelal fingers).

- The remaining pseudoscorpions were placed in the suborder Iocheirata (meaning “poison hand” and referring to the presence of a venom apparatus in the chelal fingers).

- Within the Iocheirata, the Neobisioidea were hypothesized as the sister-group to the remaining taxa. This is in contrast to the classifications in which all pseudoscorpions with separate metatarsi and tarsi in each leg were placed in the Diplosphyronida (e.g. Chamberlin, 1930, 1931) or Neobisiinea (Beier, 1932).

- Recognition of the superfamily Olpioidea for Olpiidae and Menthidae. These families were previously treated within the Garypoidea by previous authors.

- Transfer of the Cheiridiidae and Pseudochiridiidae (part of the Cheiridioidea) to within the Garypoidea.

- Recognition of the superfamily Sternophoridea for Sternophoridae. This enigmatic family was previously regarded as a member of the Cheiridioidea by Chamberlin (1931) and all subsequent authors, despite Chamberlin’s misgivings regarding this relationship.

- Harvey's proposed phylogeny of the pseudoscorpion order (1992)

Subsequent changes

To fully clarify the current state of pseudoscorpion phylogeny and classification, the following alterations have been proposed since the publication of Harvey (1992):

- Judson (2000) disputed the synonymy of the Cheiridioidea with the Garypoidea, and revalidated the Cheiridioidea for Cheiridiidae and Pseudochiridiidae.

- Judson (2004) proposed that the Garypinidae — previously a subfamily of the Olpiidae — be recognized as a distinct family.

- Judson (1992, 1993) removed Pseudotyrannochthoniinae from Chthoniidae and treated it as a separate family of Chthonioidea.

- Murienne et al. (2008) presented the first molecular phylogenetic analysis that mostly corroborated the previous trees and alterations. However, several anomalies were detected.

Fossil Fauna

The majority of recorded pseudoscorpion fossils are derived from Tertiary ambers as Baltic, Romanian, Mexican, Dominican or Chinese deposits. Only four pseudoscorpions have been recorded from Mesozoic ambers, Amblyolpium burmiticum [redescribed by Judson (2000)], and Electrobisium acutum from Myanmar, Heurtaultia rossiorum (Judson, 2009) from France, and an undescribed chernetid from Canada (Schawaller, 1991a). Other Cretaceous pseudoscorpions have been reported from Lebanon (Whalley, 1980), U.S.A. (Grimaldi et al., 2002) and France (Perrichot, 2004).

Of greatest interest was the discovery by Shear et al. (1989) and Schawaller et al. (1991) of a remarkable pseudoscorpion from the Palaeozoic–Dracochela deprehendor. Despite its great age, it shares numerous similarities with modern pseudoscorpions.

This website contains published data up to the end of 2011.